I’ve come to believe that without friends or acquaintances to open doors it’s almost impossible to achieve personal goals. Looking at my own career in education and journalism, I instantly identify four people without whose help I would have stood still or slid backwards. What follows are brief profiles of these men and the circumstances where I needed a lifeline.

I. Ragnar Thaning

In 1963 when I was 19 I traveled from my home in west Michigan to Seattle and then San Francisco determined to find work on a ship and explore the world. Seattle turned out to be a dud, a study in frustration. I learned that American ships were unionized, that you first needed seaman’s papers from the coast guard. Then you registered with the National Maritime Union and waited in a union hall to be called. Jobs were scarce and it was apparent that it would take weeks if not months to get a ship. I was operating in a three-month summer vacation window.

I retreated on a Greyhound bus to my uncle and aunt in Eureka, CA on the Pacific coast near the Oregon line. They boosted my spirits and after a few days saw me off for San Francisco.

Two years earlier in San Francisco with my parents, I had called on Ragnar Thaning, a shore captain with the General Steamship Company. Later back in Michigan Captain Thaning sent me an encouraging letter.

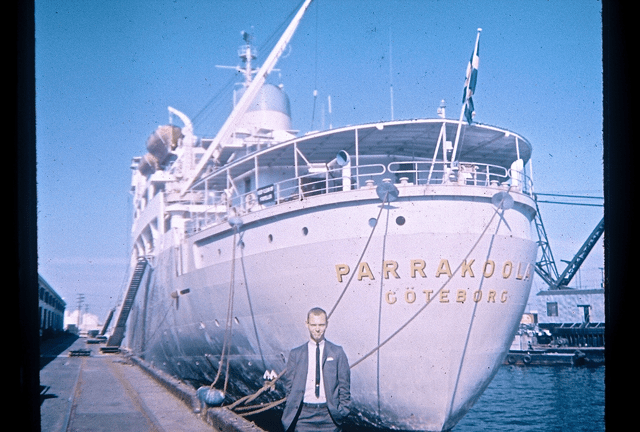

Upon arriving in San Francisco I telephoned Captain Thaning. The next day I had a message from him at the YMCA Hotel on Turk Street where I was staying. He said a Swedish ship had come in and needed crew. If I was prepared to travel to Australia, be gone six months, and work for $25 per week, I could sign on as a deckboy aboard Parrakoola, a general cargo ship currently collecting outbound cargo at west coast ports. I was to report the next day to the ship’s captain at pier 37.

I visited the gleaming, almost new MS Parrakoola at pier 37, was interviewed by the chief mate, and got the job. I was thrilled beyond description. It was July first and I had been gone from home three weeks. It was the best thing that had ever happened to me

In terms of this first lifeline, I’m not sure what would have happened without Captain Thaning and the good luck I experienced in San Francisco. There were still two months of summer vacation remaining. Would I have remained in SF? I don’t have a clue. In the end I was gone from Michigan nearly six months, missing an entire semester at Western Michigan University. That was a mere inconvenience given the rich experiences I had aboard the MS Parrakoola.

II.David DeShon

In 1968 at the height of the Vietnam War teaching jobs were plentiful. In the spring of that year and nearing completion of my master’s in economics at Western Michigan, fellow graduate assistant Bill Cooper and I traveled by car to the Midwest Economics Association jobs fair in Minneapolis. There both Bill and I received offers to be instructors of economics at Northern Michigan University at Marquette in Michigan’s upper peninsula. We jumped at the chance, eagerly accepting jobs that paid $7,300 for the academic year.

Bill and I rented a ranch-style house overlooking Lake Superior and each of us got seriously involved in teaching principles of economics. At that time there was controversy on campus about the closing of a government-funded Job Corps education and training center that was one of President Lyndon Johnson’s great society programs. Bill and I got involved in student protests opposing the closure and that led to activist students starting a newspaper called Peace. We were faculty advisors and much of the editorial work was done on weekends at our place. During the harsh winter months our home became something of a refuge for student activists.

What we didn’t know then was that our landlord had told the university president that Bill and I were radical leftists—even communists–and that posters of Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong hung from the walls in the garage. In addition, I learned much later, the FBI had been alerted and agents rented a nearby home and actively surveilled us for several months.

In the spring of 1969 Bill and I each received offers to return to Kalamazoo as instructors of social science at Western, our alma mater. The pay was higher, $8,300. We were ecstatic and celebrated this unexpected huge opportunity dancing and rolling on the front lawn. Our Dutch friend from Upjohn Pharmaceutical in Kalamazoo who was visiting at the time observed our celebration and said he had never witnessed such joy. Bill’s girlfriend and future wife had remained in Kalamazoo, so he was eager to get back. In fact, each of us and other faculty friends were eager to move on from remote Marquette and its harsh winters, hundreds of miles from any major city.

The person extending the job offer was David DeShon, a Wisconsin PhD economist, chairman of social sciences in Western Michigan’s school of general studies. Bill and I had worked with Dave in our respective masters’ programs. Dave wanted to shake up general studies and believed our background and enthusiasm would be helpful. What neither Bill nor I knew at the time was that the chairman of the economics department at Northern would not have extended our contracts for a second year. Given the turmoil on campus I’m pretty sure that the department chairman was under orders to get rid of Wood and Cooper, his troublemaking junior faculty.

I don’t have any clue of what I would have done had Dave DeShon not thrown me a life line. Would I have sought another university teaching job? Probably. Would I have begun a dreaded PhD program in economics as Bill eventually did? No way.

David DeShon, 1960s photo

III. George Palmer

Without doubt this next episode was the biggest personal challenge I’ve faced.

In December 1971 I typed out a letter to Dave DeShon resigning from my teaching position. Immersed in the anti-Vietnam war movement and worn out from setting up an experimental living-learning program in teacher education, I wanted out. The gigantic May Day protests in Washington six-months earlier marked a high water point in America’s cultural revolution. But 200,000 protesters and 13,000 arrests over a three-day period (I was not among those arrested) had not stopped the war nor provided any sign of eventual success. Like other refugees from the movement I figuratively headed for the hills, embracing nature and friends, lying low until the bad times and Richard Nixon passed.

Over the next two-and-one-half years I lived in Stamford, CT working successively as a barman, waiter, grounds keeper, shipping clerk and substitute teacher. During this period of drift I crafted a plan to get to South Africa where I could become a journalist reporting on the end of apartheid. Then came a precipitating event, the April 25th, 1974 revolution in Portugal, overthrowing four decades of self-declared fascism. The junior officers who carried out the bloodless coup declared they would end the colonial wars in Africa and bring independence to the vast Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique. This was it. If white-rule South Africa, Southwest Africa and Rhodesia were to lose their protective buffers from the rest of Africa, minority rule was finished. I wanted to be there to witness this historic shift.

My partner Shellie and I sailed from Brooklyn on a Danish freighter bound for Cape Town two weeks after Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in August 1974. It was a bold undertaking as neither of us had job offers and we had very little money. As we sailed away I was cognizant of the words of our friend Don Gardner, a French instructor at Western, when bidding us farewell. “This adventure of yours,” he said, “could turn out to be really good or really bad.”

After a 19-day voyage the MS Diana Skou arrived in Cape Town. When we passed Robben Island where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned we stood at the stern of the ship and hurled a burlap bag of a dozen books we either knew or thought were banned in South Africa into the sea.

The southern Africa adventure started badly and nearly came to an abrupt early conclusion. After a pleasant week in Cape Town we went by train to Johannesburg and I began a forlorn search for work. We had spent virtually all of our savings booking our passage and had only $300 or $400 of remaining cash. I carried with me several letters of recommendation, had written various corporations and assumed I would quickly be offered professional employment. How wrong I was. It must have been that prospective employers detected a troubling gap in my resume. Why had I given up university teaching at the end of 1971? Who was this guy Barry Wood, why is he here?

For nine utterly frustrating weeks I pounded the streets of Johannesburg going from mining companies, to banks, to shipping forwarders, to colleges. Nothing. At one point, having been turned down by the economics department at the University of Witwatersrand, we got welcome relief correcting 200 term papers for which we were paid the equivalent of $200.

But with every passing day our spirits sagged along with our meagre finances. I then developed what I thought was a doable fall back plan. We could hitch hike to Durban, crew on a yacht, reach Mombasa, Kenya where a ship called the Karanja traded between east Africa and Bombay. We could return home having at least gone around the world. Shel said no way. She had come this far but would go no farther.

Then came the most important break I’ve ever had. I was introduced to a writer at the Financial Mail magazine, a weekly modeled on its former owner, the London Economist. The FM was arguably the most respected, comprehensive and courageous anti-apartheid publication in South Africa. I was introduced to deputy editor Graham Hatton, who took me under his wing. We were invited to his home for Sunday tea. Calling me a piece of driftwood that had washed ashore, Hatton took me into editor George Palmer’s corner office in the 9th floor of the Carlton Centre, a new 50-story building in downtown Joburg. Hatton departed and I stated my case to Palmer, who trained as a Royal Air Force pilot in World War II. He was a demanding editor with a fearsome reputation.

After ten minutes Palmer said it wouldn’t work and I was done. Crushed, I slunk back to Graham’s office and shared my sad story. To my astonishment, Hatton forcibly responded saying, “don’t’ take that!- -go back and tell him he’s made a mistake.” Stunned but with nothing to lose, I marched back to the editor’s office and said firmly, “Mr. Palmer, you’re making a mistake. I can produce good work for you.” He listened, there was a long pause, then he slapped his hand on the table and replied ”all right, I’ll give you a two-month trial at R600 per month.” I was ecstatic. That night Shel and I celebrated with champagne and a fine meal at a Portuguese restaurant.

That was a turning point in my life, a launch pad for a 40-plus year career in journalism.

George Palmer in the 1970s

From George Palmer and the talented writers at the FM I learned to be a journalist. Over the next two years I was sent on news gathering trips to Mozambique, Angola, Namibia and Rhodesia. I wrote, among many others, articles about the plight of farm workers, student activists, trade unions, and went underground at a Free State gold mine.

The FM’s labor editor, John Kane-Berman, instrumental in getting me to the FM, wrote in his memoir that Palmer was among the most courageous of editors fighting against apartheid. He built a team of excellent writers who were proud to be working for the FM and George Palmer. Kane-Berman, a Rhodes scholar, described the atmosphere at the FM as being “as intellectually stimulating as Oxford tutorials.”

As to what would have happened had I not gotten the job at the Financial Mail, I have no idea. My best guess is that I would have persevered and eventually found something. Shel and I had invested too much to have turned and run.

Of course, it all worked out and I even earned the respect of George Palmer, proof of which came in the following letter raising my pay.

IV.Alan Heil

Our time in southern Africa was formative and intense. Shel too began a career in special education, having secured a counseling job at Cross Roads school in a Joburg suburb. Suddenly we had money and eagerly explored what for us was a very different, often alien world. We hitch hiked to Swaziland near the Mozambique border. We spent time in mountainous Lesotho, an independent land enveloped by but never part of South Africa. We traveled to exciting, richly different Mozambique, which was headed towards independence from Portugal. Likewise, we flew to the breakaway British colony of Rhodesia where a passenger jokingly said “we’ll soon be landing in Salisbury. Please set your clock back ten years.”

But most impactful was our long journey from Johannesburg, by train the length of Botswana to Livingstone, Zambia and then a 900-mile hitch hiking jaunt from Zambia’s Victoria Falls through the capital Lusaka all the way to Lake Malawi. There in northern Malawi we were dropped off at the Fish Eagle Inn, a charming colonial-style retreat where activity stopped when the BBC’s Focus on Africa program came on at 6 p.m. Traveling on to Malawi’s new capital of Lilongwe we flew back to Joburg and the stifling strait jacket of apartheid South Africa.

Despite the horror of racial segregation, which I imagined to be akin to the ante-bellum American south, I was engaged in a thrilling new career. I was learning to write, to produce copy under deadline pressure, and experiencing realities unknown to most Americans.

Southern Africa was part of the cold war between the Soviet Union and China on one side and the US and Western Europe on the other. Angola, rich with oil and relatively advanced economically, became independent in November 1975, meaning there was soon increased focus on the guerrilla war in Rhodesia, which geographically is perched between the two former Portuguese colonies. I was sent up to the capital of Salisbury, subsequently renamed Harare, to investigate the country’s illicit, lucrative tobacco trade. Trailed by Rhodesia’s special branch police, local correspondent Michael Holman and I notified George Palmer of the situation. He ordered me back to Johannesburg. Then there was Namibia, called Southwest Africa at the time, where South Africa with the continent’s most formidable army was fighting the Swapo liberation group along the Angolan border.

As a writer at the highly regarded Financial Mail, I and other writers had an expense account and could take people to lunch. When dining with the head of the US Information Service in Johannesburg, he said casually that he been called by NBC News in London inquiring about American reporters in the region who could do radio. With that welcome tip, I called NBC and was given a chance to be a foreign correspondent broadcasting on their 24-hour news operation in the US. My initial assignment was Mozambique independence. It was exciting being in Mozambique on June 25th, 1975 when amid a driving rain, after nearly five centuries the green and red Portuguese flag was lowered and the Frelimo liberation group was handed control over this vast territory bigger than California. It was my first radio broadcast and soon I was filing multiple radio reports each week for NBC.

When Soweto exploded on June 16th, 1976, I was ordered to get to Soweto as quickly as possible. Shel, then a master’s student in Ann Arbor, was in Joburg. We got in my old Ford Escort and headed for Orlando East in deep Soweto. As whites were not allowed in African townships, we got in by driving around a slag pile from a gold mine, a route I knew from a previous FM assignment. To my knowledge, I was the only American reporter in Soweto on the first day of the student uprising that went on for weeks, incurring many deaths and thousands of detentions. (June 16th is now a national holiday in South Africa.) Shel and I took shelter at the USIS library in Orlando East and watched defense force Puma helicopters disgorge troops on an adjacent soccer field.

Thus began months of nonstop reporting. At our Hillbrow apartment I kept a bottle of Johnny Walker red on the counter next to the phone that constantly rang from London or New York. In South Africa the student protests spread to Cape Town and Durban. And outside the country the South Africans were fighting Cuban troops on the Angolan border. I went with other reporters on a defense force press facilitation flight to northern Namibia, returning to Pretoria the same day.

While it was exciting to be a foreign correspondent on what felt like the front line of history, I was becoming frazzled, living too close to the edge, drinking and smoking too much. My NBC work was so overwhelming that I resigned from the FM but George Palmer kindly allowed me to pay rent and keep my office in the Carlton Centre.

When you’re young you think you’re invincible but of course you’re not. I was living a frantic life, traveling most weeks, reporting and filing stories multiple times each day. By March 1977 I knew I had to get out and it was then that a lifeline arrived, from Voice of America in Washington. About the time of the Soweto uprising VOA asked me to file stories for them. I readily accepted, drawn to having two and a half minutes of air time instead of the typical 30-second spots on NBC. In early 1977 I was invited me to join VOA as a full-time employee based in Washington. I jumped at the chance. I was desperate to get out, having spent three full years in southern Africa.

This is my fourth lifeline and it involved two people—news chief Bernie Kamenske, and Alan Heil, the head of news and current affairs. Bernie was a legendary figure at VOA—rotund, partially crippled, with a Boston accent and unique opaque way of speaking. Bernie had heard me on NBC and ordered his Nairobi bureau chief to go to Joburg to check me out.

Alan Heil, VOA chief of news and current affairs

The VOA job changed my life, the launch of a 30-plus year career as a correspondent in Prague and economics editor in Washington that took me to five-dozen countries worldwide. In conclusion, one thing is sure. I could not have moved forward without essential lifelines. #