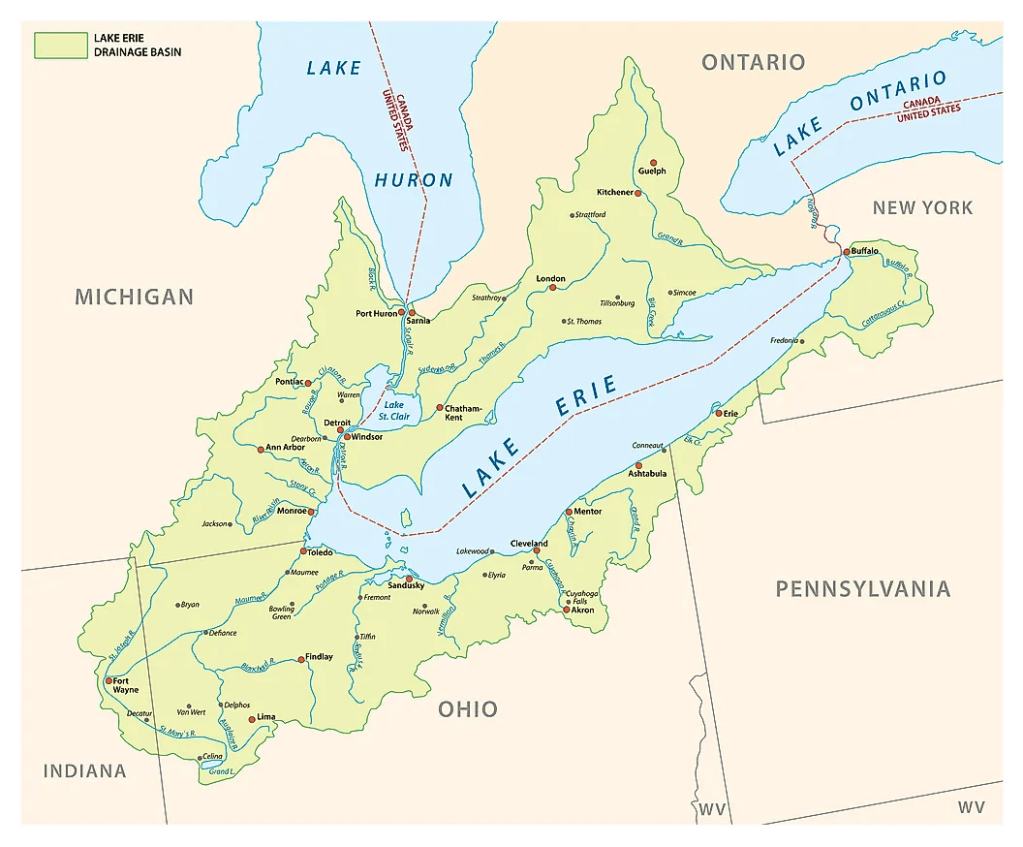

One hundred fifty years ago life on what was then the American frontier was different in ways we can barely imagine. This is the true story of a young man who left his home in northern Ohio to seek a new life in west Michigan.

A long time ago, before America’s Civil War, 18-year-old Solomon Miller, was bored living in northern Ohio. He wanted to join his seven older brothers and sisters who had migrated west, to Michigan, where you could buy land for $5 an acre and farm fertile fields growing corn and wheat once trees and brush were cleared away. Solomon was well built, six feet tall, and excelled at the popular school yard sports of boxing and wrestling.

After the winter snows had melted in April 1851, Solomon tucked his valuables in a backpack and trekked two days from Kent to Cleveland, the Lake Erie port that was becoming Ohio’s biggest city.

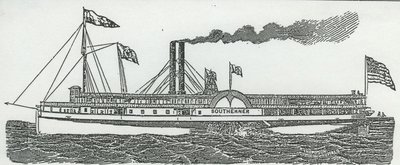

Paying a $2.50 fare, Solomon joined 150 immigrants on the five-year-old steamship “Southerner” bound for Detroit, 168 miles away. Most of the passengers had come from New York via the Erie Canal headed for west Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Their trunks lined the lower deck one flight down from the passenger cabins.

The Southerner set out that evening amid a howling gale. The west wind made the big lake rough prompting the captain to steer close to the Ohio shoreline. At Lakewood only 30 miles from Cleveland, the roaring wind blew the Southerner against a rock, the collision tore away the guy wires holding up the twin smoke stacks. They crashed onto the deck. Luggage was swept overboard. Amid panic the crew and male passengers sprang into action collecting bedding and mattresses, anything they could stuff into the gaping hole to keep the Southerner afloat.

It worked. And surprisingly, the steam engine kept chugging and the paddle wheel kept turning. The ship limped on towards Detroit. At 4:30 in the morning the boiler gave out and the Southerner was adrift. Help soon arrived. A smaller vessel, the Arrow, on its regular run between Detroit and Toledo, threw lines to the Southerner and towed the bigger ship into Trenton just south of the Detroit River. There the passengers went ashore and made their way to Detroit. Miraculously no one was killed or injured but the near disaster was featured prominently in newspapers.

Solomon Miller, like other travelers from the Southerner was bound for Kalamazoo, 150 miles west. The new Michigan Central railroad ran a daily train along the line that eventually would reach Chicago. The eight-hour journey to the railhead in Kalamazoo was a two-coach train pulled by a wood-burning engine traveling 15 to 20 miles per hour.

Nathaniel Currier, typical late 1840’s train

In Kalamazoo Solomon Miller visited the land office, getting the location in Allegan County where his pioneering family had settled. Before and after the great depression of 1837 land offices were very busy places. Amid rampant speculation, in boom years it was not unusual for property prices to double in 12 months.

Not wanting to wait for the three days a week stage coach, Solomon walked the 28 miles to his destination, Dorr township in Allegan county.

There things went well. Solomon cleared land, harvested wheat, and worked at the gypsum mine near Grand Rapids. However, he was struck by a falling tree that mangled his left hand. He married a school teacher and daughter of a Congregational preacher, Mary Sophronia Hess, whose family had immigrated from Ithaca, New York.

When the Civil War began and thousands of Michigan men enlisted or were drafted to put down the rebellion, Solomon was rejected because of his disability. He became a sutler handling horses and followed the army to Indiana. But when he was told he would be in charge of mules he quit and returned to Michigan.

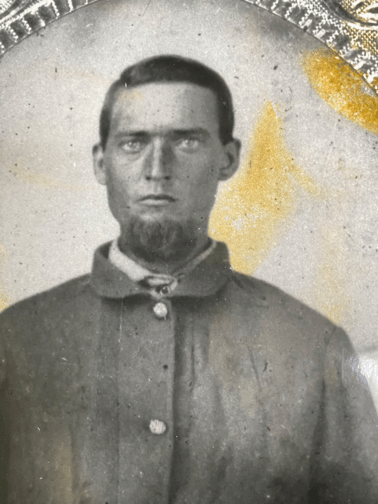

His wife’s younger brother Artemus Hess enlisted in the 17th Michigan Infantry, which became known as the Stonewall Regiment because of heroic action during the Battle of Antietam in 1862. A year later near Knoxville, Tennessee, Private Artemus Hess, 28 years old, was killed by a Confederate sharpshooter.

Artemus Hess, before enlisting in US Army

In 1882 word reached Solomon and Mary Miller that their daughter Amy had been abandoned by her husband who was a lumber jack in the pine forest in Edmore, Michigan. Solomon organized a team of horses and drove a wagon 78 miles to Edmore to bring his daughter and two young children back from the lumber camp. The father’s subsequent efforts to persuade his family to return were rejected.

In addition to his physical prowess, Solomon Miller was known as a gifted story teller. That was a strength but managing money was a weakness. Solomon’s entrepreneurial ventures on Grand Traverse Bay came to naught and the money he had obtained from his wife was lost.

Michigan pioneers Solomon and Mary Hess Miller rest in modest graves at Dorr in Allegan County. #