It’s the cliché with the ring of truth—cultural change in America begins in California. And so it was with our cultural revolution. Not the destructive class struggle of Chairman Mao, but a revolution in consciousness—a new way of thinking, activism and questioning.

Ironically from today’s perspective, it began with the free speech movement at UC-Berkeley in 1964. Fresh from the Mississippi Summer freedom project, student Mario Savio tried to raise money for the civil rights movement but was prevented from doing so by a ban on campus political activity. Protests took hold and in December several hundred students were arrested. So began the free speech movement that triggered a decade of activism on American campuses.

It was more than free speech. Opposition to the war in Vietnam, military conscription and demands for civil rights were battle cries.

Steadily from 1965 until the end of the decade a counter-culture took shape. Protests and challenges to authority were a departure from the lingering mindset of conformity. Protesters and hippies, thrilled with discovering the expanded consciousness induced by marijuana and LSD, felt empowered. Resistance to the war and the draft created solidarity, uniting dissidents nationwide.

Fundamentally important was the evolution in rock music towards deeper meaning, which exacerbated an ‘us versus them’ mentality. Dissidents were those open to new ideas while others were stuck in the past. Bob Dylan wrote, “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr. Jones.” More from Bob Dylan who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

The line it is drawn

The curse it is cast

The slow one now

Will later be fast

As the present now

Will later be past

The order is rapidly fadin’

And the first one now

Will later be last

For the times they are a-changin’

Beyond this iconic poetry there was a shift in Beatles lyrics, evident in the 1966 Revolver album.

Turn off your mind

Relax, and float downstream

It is not dying

It is not dying

Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void

It is shining, it is shining

That you may see, the meaning of within

It is being, it is being

That love is all and love is everyone

It is knowing, it is knowing

That ignorance and hate may mourn the dead

It is believing, it is believing

But listen to the color, of your dreams

It is not living, it is not living

Or play the game “Existence” to the end

Of the beginning, of the beginning

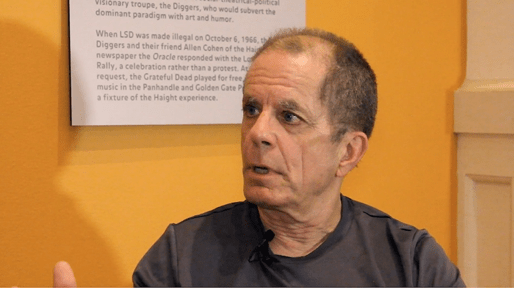

San Francisco Bay Area historian Dennis McNally spent two decades as publicist for the Grateful Dead band. He curated a photo exhibit on the 1967 Summer of Love. “The counter-culture of the 1960s,” he says, “was transformative. It wasn’t just free love and drugs. It was political protest, racial justice, redefining sexuality, organic food, environmentalism, yoga—fringe issues then, main stream today.”

Equally significant were bold experiments in education—a free schools movement emerging from Berkeley. Respected educators like John Holt, Jonathan Kozol, and George Dennison, broke with the past and challenged traditional teaching methods. Books and articles championed student centered learning. Joseph Tussman’s Experiment at Berkeleyoutlined new structures, at once advocating academic rigor while promoting small group seminars long a fixture at Oxford and Cambridge.

It was cultural change that reimagined the past and saw optimism and joy in new structures, a movement that could change the world. Possibilities seemed endless. The essence of peace and love was “think for yourself, challenge the establishment.”

Hope and solidarity were forged at anti-war and civil rights protests which periodically in Washington, DC brought together students and dissidents from across the land. There was the Pentagon march in ’67, the war moratorium in ’69, protests over the 1970 shootings at Kent State and Jackson State, and finally May Day in 1971, an effort to shut down the city in which 12,000 protesters were arrested over a three-day period.

Woodstock in August ’69 was a celebration of a still growing counter-culture. It seemed then that protests were having an impact as American involvement in Vietnam began to wind down and the hated draft was replaced with a lottery.

While not apparent to all, May Day ’71 was the high-water mark, the culmination of the movement. Yes, there had been progress but also exhaustion. Resistance to change was strong.

Rock musicians and artists, so vital to counter-culture growth, lost momentum. Where Dylan and the Beatles had underscored optimism, now the tune was despairing. The Beatles having broken up, John Lennon sadly proclaimed, “the dream is over.” Don McLean’s 1971 American Pie, despite the singer having no direct ties to the counterculture, was an anthem of defeat: it was “the day the music died.” The symbolism was unmistakable.

Why did the cultural revolution—the counter-culture—wither and die? I think a principal reason was the end of conscription and the approaching end of American involvement in the Vietnam war. During that decade long conflict two million American boys had been drafted. With the draft gone, a main cause of protest was removed. In the 1972 presidential election the nation rallied not to peace candidate George McGovern but to incumbent Richard Nixon, who carried 49 of 50 states.

The ‘70s were a sad time of reflection. Former hippies and counterculture people were retreating to rural areas or making peace with the establishment. It was not a happy time.

For me, from my perch in Kalamazoo where I was an instructor of social science the cultural revolution ran—approximately– from 1965 to 1971, six wonderful, exciting years. After May Day and a time in Paris I gave up university teaching and also the notion of getting a PhD. I retreated to Connecticut and attempted to write a biography of Lincoln Steffens, the muckraking journalist who became famous when Teddy Roosevelt was president. I survived as a bartender, waiter and substitute teacher, the planned book having come to naught. Ultimately, I embraced journalism and spent three years chronicling the end of colonialism in southern Africa.

So, why is so much made of the cultural revolution in China instead of the USA? Mainly, I think, because Mao’s minions grabbed hold of the term while journalists at the time could do no better than describe the US variant as a mere hippie or dissident movement that fizzled.

What happened during China’s cultural revolution was unmitigated disaster, a decade of total disruption with schools and enterprises closed, with thousands of “capitalist roaders” brutally dispatched to the countryside. It was very violent, a period in which at least half a million people lost their lives. The Chinese cultural revolution was an effort by the aging Mao Zedong to consolidate his flagging power by mobilizing youth to purge the country of residual capitalist tendencies. The chaos ended only with Mao’s death in 1976.

Compare the two movements. China’s cultural revolution was top down, organized and directed from the top. Independent thinking was forbidden. In the US change was bottom up and not surprisingly its impact is more enduring. It was the American cultural revolution that gave rise to the environmental movement, the organic food movement, to liberalizing sexual mores. American students today find it easier to question authority, a legacy of the 1960s.

To sum up, the US the cultural revolution was about freedom. In China it was about control. No wonder the Chinese—from the communist leadership to what used to be called the masses—repudiate Mao’s great cultural revolution. #

Aside from protests and being instrumental in creating an alternative teacher training project in Kalamazoo, Barry’s most direct involvement in the cultural revolution came during a summer in Berkeley in 1970 and days of activism in DC and Paris.